For a long time he was the world’s best-known living French artist, but less for his work than for giving his name to a big annual film event. Museums made him pay the price of such celebrity and, with rare exceptions, the avant-garde quickly turned its back on him. In 1991, when asked by Télérama’s art critic, Olivier Cena, “What’s it like being a well-known and media-friendly artist?”, César (1921–98) replied, “Known to whom? I’m 70 years old and the Pompidou, the top museum in the country, has never exhibited my work.” Today he’s finally getting a Pompidou retrospective, but it’s less to do with a legitimate desire for rehabilitation than with the 20th anniversary of his death. But that’s how it goes with César, whose life was a series of encounters: those that happened (between tools and materials), and those that were put off (between his work and the big art institutions).

He was born César Baldaccini, in Marseille, to Italian parents, and studied at the Marseille and Paris Écoles des Beaux-Arts in the 30s and 40s. In 1960 he joined the Nou ve au x Ré a liste s, a group founded by the legendary art critic Pierre Restany in Yves Klein’s home. But César later confided to Otto Hahn, art critic of L’Express, “My alliance with the Nouveaux Réalistes was tactical, resulting from my distress and solitude.” A solitude that was caused by the singularity of his work and the unique, and paradoxically marginal, position in which his fame placed him.

César is indeed a sculptor and with him the feeling of exactitude prevails over absolutely everything else.

César’s oeuvre is a question of encounters: with materials first of all, in particular expanding polyurethane foam, which gave birth to his Expansions. The first, realized in public in 1967, were cut up by César and offered to the audience as little fragments in a sort of involuntary prefiguration of “relational aesthetics.” Because the foam wasn’t stable, César developed a technique that allowed him to harden the surface of his Expansions, which he stratified, sanded, lacquered, covered with glass fibre, sanded again, then covered with successive layers of lacquer, producing a spread-out volume that seemed to radiate light from its bowels. These Expansions, wrote the art critic Catherine Millet in 1986, “opened a new chapter in modern sculpture, that of free form and works founded on the very properties of materials” (25 ans d’art en France, 1960-1985, Larousse).

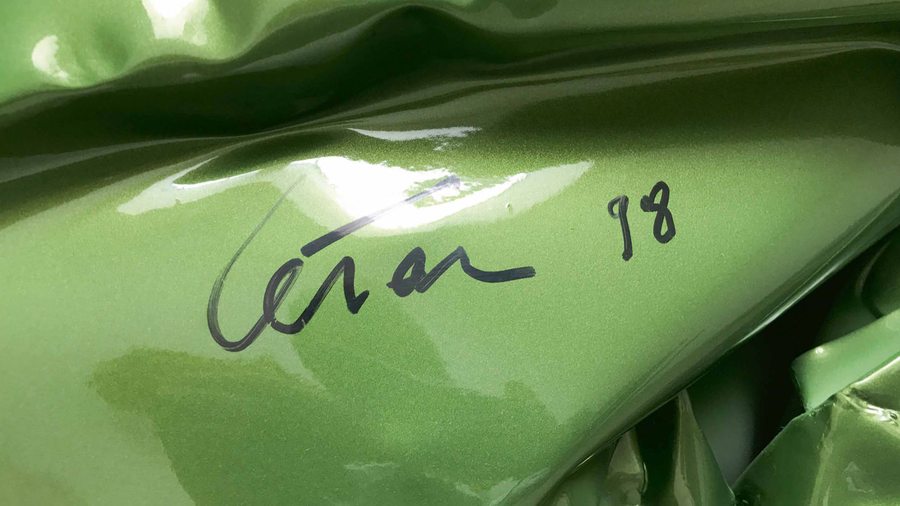

A few years earlier, it was the unexpected encounter with a hydraulic press at a scrap-metal merchant in Gennevilliers that pushed César’s work far from the classic forms of his début towards a new destiny. From this machine would burst forth his Compressions, which César initially envisaged as plinths for more traditional sculptures, but whose intrinsic sculptural quality he soon began to intuit. Soon enough he produced the large Compressions entitled Trois Tonnes which he presented at Paris’s Salon de mai in 1960. “It was a lightning bolt, straight away I wanted to use it. First of all I used it in a rough way, if you will. The press went beyond my desires, it seized the material, crunched it up and transformed it into enormous calibrated balls of varying weight. I was blown away by this machine that transformed cars into packets of scrap metal of over a tonne.” As of the following year, he learnt to “direct” these Compressions: “Only put in the bumpers, the bonnet hoods, and the wings. I’d like a black car, two red bonnets, 12 bumpers.” They would become, for better or for worse, the emblem of his oeuvre throughout his career. Pie r re Restany was still amazed by his final Compressions, made in 1998 (for example Suite milanaise), and commented on how César demonstrated his work as a sculptor, organizing more than usual the circulation of air between the squashed and scrunched sheets of metal. What’s more he dared to submit them to an almost sacrilegious gesture, sending these final Compressions to a car paint workshop where they were coloured metallic green, violet or gold, thereby obliging them to own up to their decorative dimension. But he also distanced himself from this gesture by leaving them on their wooden paint-shop pallets when they were exhibited.

Because in 1995 Catherine Millet, curator of that year’s French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, committed a capital crime in the eyes of the Association française d’action artistique (AFAA), the organizing institution, by preferring César over all the avant-garde artists from whom she was expected to choose.

In February 2015, British singer Paloma Faith received the Brit Award for best female artist, a statuette designed that year by the star figure of the Young British Artists, Tracey Emin (who had also designed the accompanying décor at London’s O2 Arena). Emin’s involvement with the Brit Awards in no way damaged her reputation, and indeed probably added to the respect that the entire profession feels for her. It was rather different when, in 1976, César accepted Georges Cravenne’s request to design the trophy that would be given to France’s film actors on the occasion of a ceremony which would, moreover, bear the artist’s name: the César Awards. As a result, César became a star, and was immediately despised by both France’s art museums and the avant-garde – with one notable exception. Because in 1995 Catherine Millet, curator of that year’s French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, committed a capital crime in the eyes of the Association française d’action artistique (AFAA), the organizing institution, by preferring César over all the avant-garde artists from whom she was expected to choose. “Choosing César was totally spontaneous. It seemed like the only choice: his work is so important in the history of modern sculpture but he had never yet been allowed the recognition he was due in his own country,” she recalls (in D’Art Press à Catherine M. Entretiens avec Richard Leydier, Gallimard, 2011). “I was harassed for weeks on end … People accused me of choosing an old fogey. When the then director of the AFAA’s ‘plastic arts’ section realized that I wasn’t going to budge, she turned towards her colleague and said in a pathetic voice, ‘What are people going to think of us?’” The shock and the affront went down very badly: “The AFAA didn’t want to run the same risk again. Today the artist is chosen by a commission which also chooses the curator, who is no longer anything more than an executor. Artistic engagement has been replaced by the consensus.”

In 1995, in the French Pavilion, César piled up 520 tonnes of Compressions, saturating the main gallery and leaving barely a metre-wide passage around the periphery. After the work was installed, César considered the effect and said simply, “There’s a row missing.” In Trieste he found a scrap-metal merchant who he commissioned to make some extra Compressions, with which he was able to raise the already imposing height of this “supercompression.” “And it has to be said that the proportional relationship with the gallery space was now perfect,” remembers Millet. “Since then I’ve always thought that it’s by this sort of demandingness that you recognize a true artist: as long as the realization doesn’t correspond exactly to the image in their heads they’ll never give up.” César is indeed a sculptor and with him the feeling of exactitude prevails over absolutely everything else. Legend has it that, after squishing up the white Rolls of a collector who had invited him to turn it into an artwork, César turned round and said to his face: “It hasn’t come out very well – I’m not signing it.”

The current Centre Pompidou retrospective has been organized by none other than the museum’s director himself, Bernard Blistène, one of the most brilliant curators in the world today, and also one of the most nonconformist. If this event pays tardy homage to the great sculptor who was César, it is first and foremost because he’s in the hands of this passionate man, even if, sadly, Blistène’s enthusiasm has not yet been picked up on by any of the world’s other big art museums.

César, la rétrospective, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 13 December 2017–23 March 2018.