American artist Avery Singer paints with the digital tools that have been developed for architecture and video games. While her portraits of robot figures might recall the science fic- tion of Tron, it would be reductive to judge her work only by technique, since it is constantly evolving in re- sponse to both the contemporary context and the history of art, which she’s well versed in thanks to her parents, who are both painters. Numéro spoke to the 33-year-old, who has just completed a giant fresco for Cologne’s Ludwig Museum, as well as signing with Swiss gallery Hauser & Wirth.

Numéro: What’s your back- ground? How much did your upbringing influence you?

Avery Singer: My background is that I’m a third generation native New Yorker. I grew up downtown, two blocks north of the World Trade Center. Educationally speaking, I’m a product of the New York City public-school system. Culturally, I grew up in a very bohemian environment: my parents are both painters who worked as film projectionists. My mom later worked as a secretary for a company in the World Trade Center and then as a graphic designer for a children’s book-publishing company. My exposure to art downtown as the daughter of artists and projectionists (my father projected at MoMA) was incredibly influential on developing a feeling of closeness to Modern and contemporary art. As I was able to see Modern masterpieces in the museum environment regularly, I feel strongly that art shouldn’t be stored away privately. Art should be publicly available to all viewers, because Modern and contemporary art exists for the museum context. My public-school education taught me my work ethic. My high school, Stuyvesant, is the most high-performing and impoverished public school in the U.S. I was one of very few non-immigrant students there. I learned my work ethic from my parents and my fellow Stuyvesant students. I then went to Cooper Union on a full-tuition scholarship, and my already solid work ethic was strengthened even more.

Do you remember your first encounter with art? What made you want to be an artist?

I don’t remember what that would have been, since I grew up in my parents’ art studios. I didn’t have my own room, instead I had a loft bed that overlooked my mom’s painting studio. We didn’t have air conditioning for a long time, so I remember hot summer nights with all the ceiling fans turned on both to cool us off and to dry the paint. I realized I wanted to be an artist when I made my first super-8 film with a camera mydadgavemeasagiftformy15th birthday. I fell in love with art at that age. I like to say that art and I have been happily married ever since. Prior to realizing I wanted to be an artist, I dreamed of being a mathe- matician or a computer scientist.

What were you looking at then, and what do you look at today?

I look at everything: I absolutely love art and artists, who devote their entire spirit, being and life to the prac- tice of artmaking. Outside of the art realm, I’m interested in image-making technologies, along with innovations in tech that change the way we see and have experiences, popular media culture, and so forth.

Do you consider yourself a painter? Is this category still relevant in 2020?

I don’t know what else I would be, other than a painter – a human being perhaps? The category of painter clearly still exists, but the looser and broader the category is, so much the better in my opinion.

What are the sources you use to make your images?

They come from a myriad of places: lived experience and noticing how I look at things and how they appear to the world. My sketches come out of 3D-modelling programmes that I use to visually construct the different figures and spaces in my work.

When did you start incorporating new technology in your work?

Probably as an art student. Though I was focused on traditional carpentry skills, with and without the use of power tools, I was interested in video art and computer modelling as well. The tech element you see in my work changes as my goals in my painting practice change.

You started out using grisaille, but more and more you’ve been adding colour. Does this change have anything to do with your evolving technique?

I simply stopped thinking about colour, which strangely resulted in my beginning to use it. I got into it and after a while became aware of it. I like that it was an unconscious de- cision on my part. You let the painting itself dictate its own direction, instead of pre-planning and executing an idea like a conceptual artist.

You often use “robot” or futurist manga characters in your work. How did these personae appear?

It started as a simple figure I constructed using the pared-down geometry I was capable of producing in my limited knowledge of the programme. The hair pattern actually came out of my attempt at depicting the peiyes [sidelocks] on a Hassidic character from a painting titled Jewish Artist and Patron. I also have a figure that is based on Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner sculptures representing a human bust.

Your characters seem lonely... Is there a link between loneliness and technology in your work?

I don’t think so much about portraying loneliness in my work. It’s probably an issue that’s at play in the paintings, but it’s not necessarily at the forefront for me.

You also produce self-portraits. How did you integrate your image into the paintings?

I made a self-portrait recently. My assistant took a photograph of me in my studio, and we collaged it into a rendering of a 3D model an artist friend of mine developed for a project we did together. This model was meant to function as satire of luxury urban development in a New York City, by proposing an expansive open-air toilet pavilion as a public park.

Can you talk about the way you install your works? How is the way you display them in your exhibitions important as a vehicle for your message?

We learn about the politics of display as art students. The way you hang your work conveys your attitude towards both the venue in which it’s hosted as well as the architecture. Architects are very utopian, in my opinion, and they design spaces that give promise to certain functions. Your role as an artist working within their framework has manifold expression. Your work hanging in a politically or economically fraught institution may speak of another.

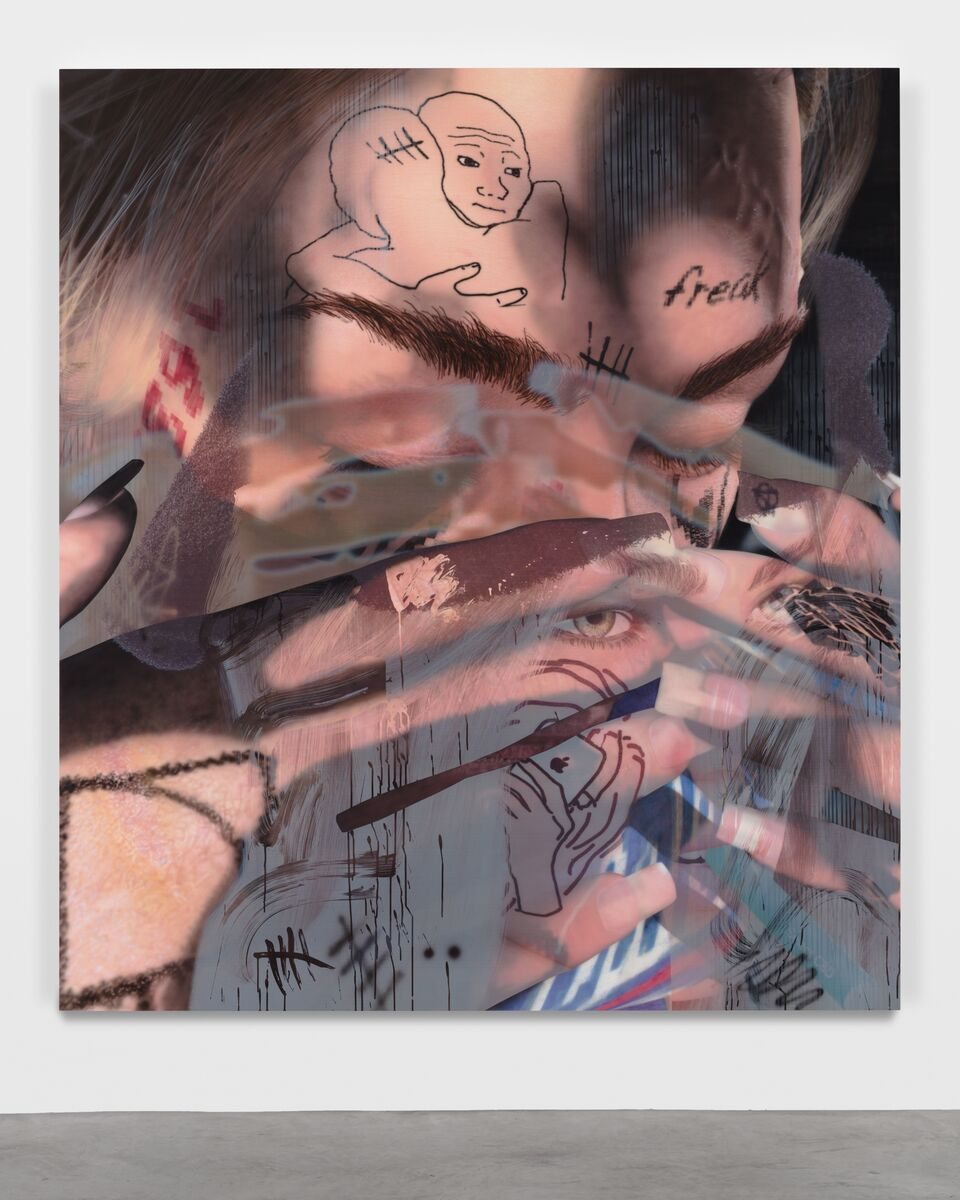

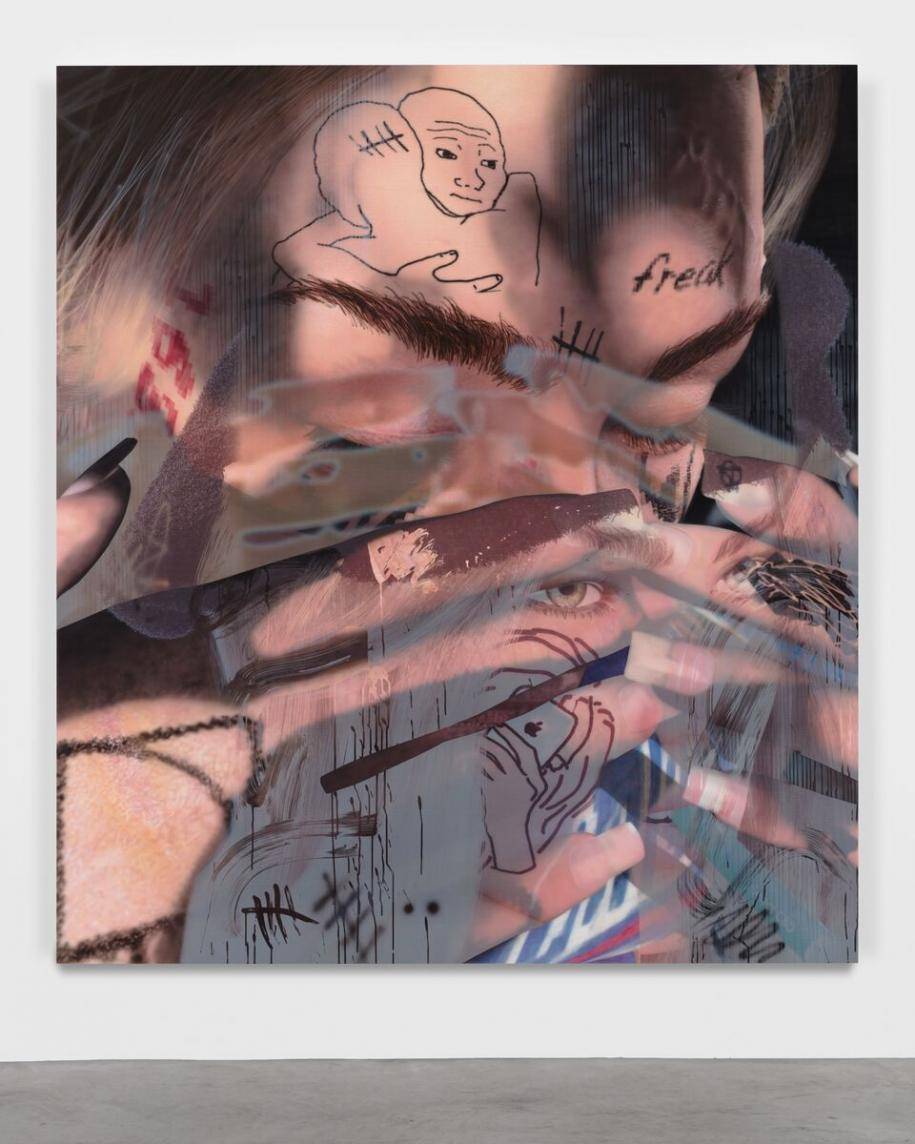

“Untitled” (2019) d’Avery Singer. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

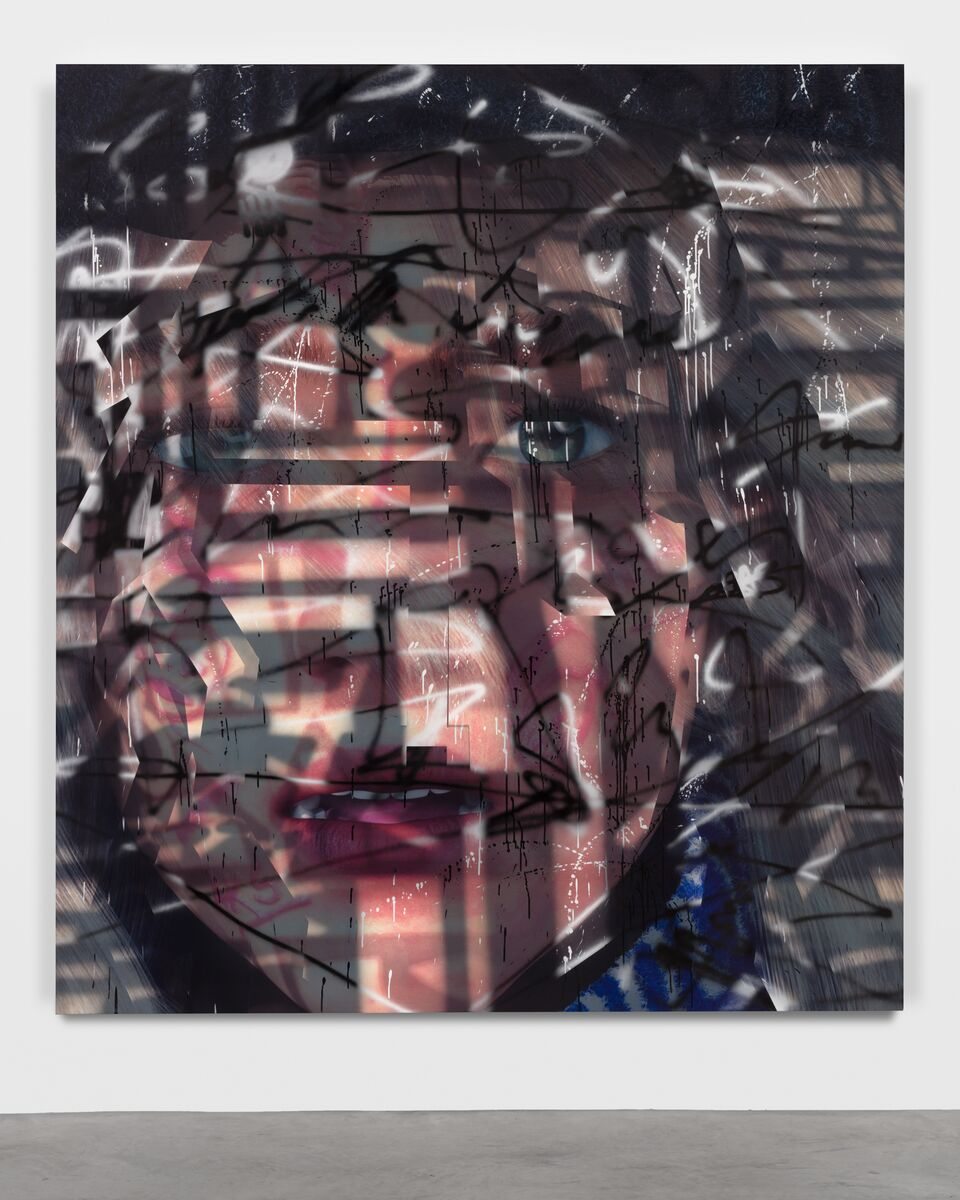

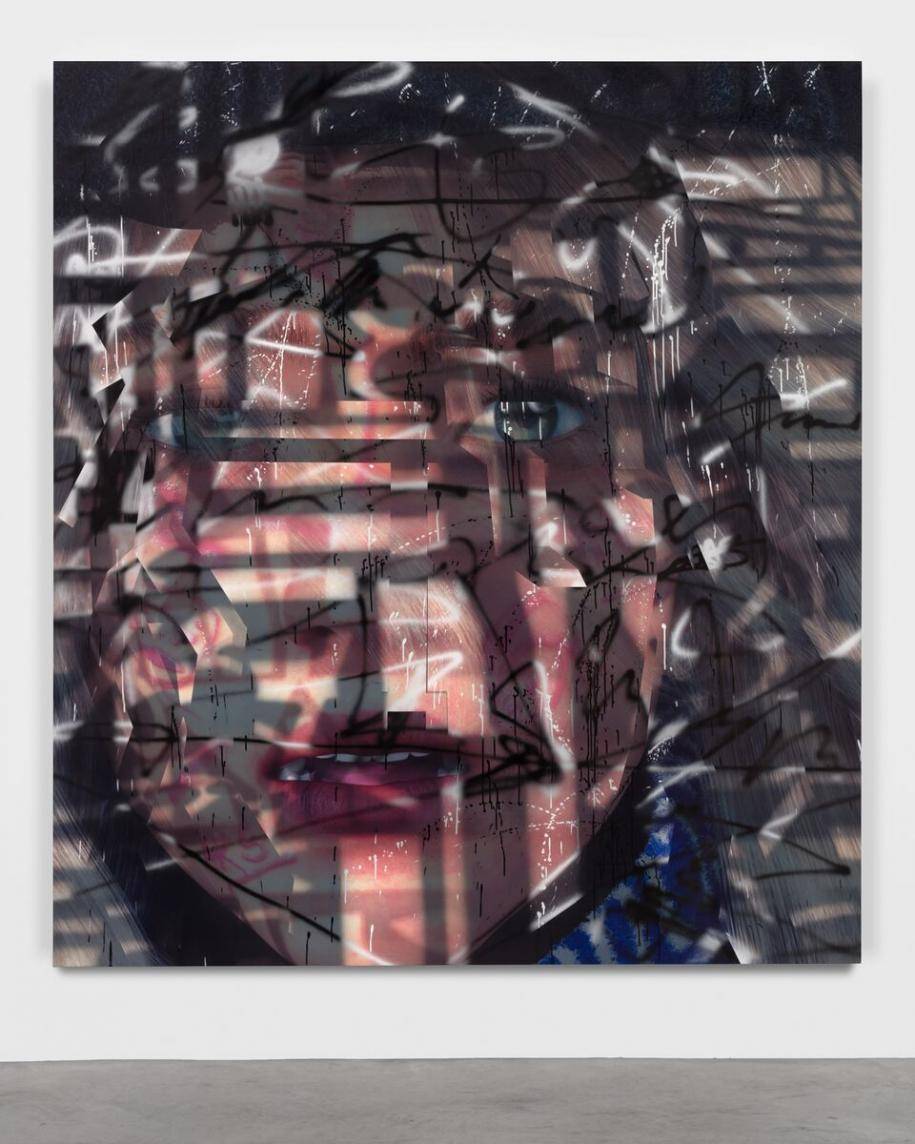

“Heir” (2020) d’Avery Singer. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

Can you talk about the Schultze Project you’ve just completed at Cologne’s Ludwig Museum? How did that come about?

Sure. This particular project is funded by the estate of a local artist, Bernard Schultze. The estate bequeathed paintings and a financial donation to the museum. Every two years, a painter is invited to produce a site-specific work with supplemental installation funding provided by the Schultze estate. In its first iteration, Wade Guyton produced a multi-panel work that portrayed scenes of the World Trade Center and Lower Manhattan. For my commission, I thought it would be a wonderful opportunity to make a large- scale panoramic work meant to be viewed from afar. I combined a series of previously used SketchUp models and rendered them in a bluetiled grid, which is a paint filter in the programme. The figures and faces camouflage with the background.

How do you find the titles for your pieces?

They have to strike me, otherwise the work remains untitled.

You work with today’s tools, but the results look somehow futuristic. How do you analyse this shift? Is the future now?

The future is the future, now is now! How would you define futuristic? For me there’s a lot of plurality in that term. I feel like my work addresses the times we’re living in.

Would you say your work fits into the “big” history of paintings?

I would hope my work makes it into the big history of painting, as well as the contemporary art of our time. Painting and art will continue to march forward – and I’m excited to be part of that trajectory.

Is there anything that you’d like to make people conscious of through your art?

I’m not sure about that. I don’t exactly know what their experience of my work is. I would like them to see or experience something that reflects on contemporary society or culture. And I would also like it if they felt they were being faced by a new approach to painting.

Did you ever feel associated with a particular community or movement? Do you today?

Not really, since I’m very much a loner by nature. And I don’t see that changing anytime soon.