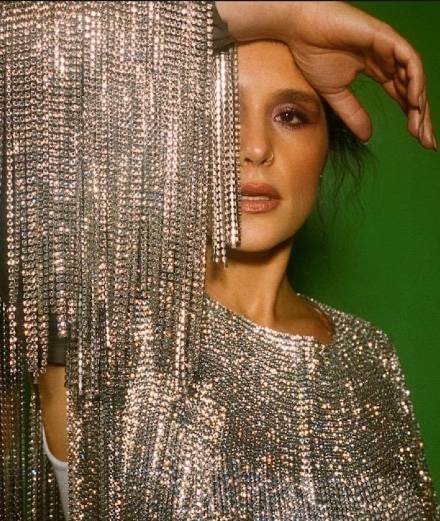

Since releasing their first album in 2015, Ibeyi, the duo formed by French twins Lisa-Kaindé and Naomi Diaz, haven’t stopped conquering the world. They’d already seduced Richard Russell – producer of The XX and Adele, who has been with them from the beginning – when Beyoncé fell under their spell and invited them to take part in her film Lemonade, in 2016. The internet went wild. And when Chanel took off for Cuba to show its 2017 cruise col- lection, it was of course to the two sisters, daughters of a Cuban father (the celebrated musician Angá Diaz), that Karl Lagerfeld turned. Because their syncretic music, which mixes sounds from electro and Cuban mu- sic, as well as jazz and soul, embod- ies the quintessence of an age which knows no boundaries nor genres. But also because their heady, mov- ing sound has a soul, which can be felt in all 12 tracks of their second album Ash, an elegant, luminous, committed disc that was one of the musical high points of 2017.

Numéro: Running through your music there’s a strong current of spirituality, in particular the Yoruba religion, which is very widespread in Cuba but which originates around the River Niger. Have you been to Africa?

Naomi: We had an extraordinary experience in Benin. We wanted to go to the Door of No Return, one of the places where slaves left for America – a place where hurt can be felt in the very air. On the way there, a woman came up to us: “You’re twins? I come from the village of twins. You must come with me. We must hold a ceremony.” Over there, when a twin dies, you have to create a figurine and feed it until the end of the other twin’s life. For our arrival, the priests had got out all the figu- rines. The whole village burst into song, lit incense, and the men banged on their chests – just like back home in Cuba. From one con- tinent to another, generations later... We were in tears.

“When I learned that I was one of the daughters of Yemaya, I immediately remembered that as a little girl I used to spend all my time singing by the sea. I dreamed of being a mermaid and breathing underwater. I cherished the feeling of well- being below the water, in a bubble, rocked by the waves in a parallel world. I was a little girl and it blew my brain.” Lisa-Kaindé Diaz

Is it true that, according to the Yoruba religion, one of you is the daughter of the goddess of water and the other the daughter of the goddess of lightning? And how is that decided?

Naomi: It’s the gods who decide, during a ceremony. The priests throw shells onto the ground and read the gods’ answers. “Is this girl the daughter of Osun?” “No.” “Is she the daughter of Ogun?” “No.” “The daughter of Shango?” “Yes.” I was the daughter of Shango, goddess of lightning. And Lisa, was the daugh- ter of Yemaya, goddess of the sea. And where our characters are con- cerned, the gods were spot on.

Lisa-Kaindé: When I learnt that I was one of the daughters of Yemaya, I immediately remembered that as a little girl I used to spend all my time singing by the sea. I dreamed of being a mermaid and breathing underwater. I cherished the feeling of wellbeing below the water, in a bubble, rocked by the waves, in a parallel world. I was ob- sessed by the idea of humans living underwater, of an Atlantis. I was a little girl and it blew my brain.

Naomi: Hayao Miyazaki’s films had a similar effect on us – Castle in the Sky and Princess Mononoke, which our father took us to see when we were seven.

Lisa-Kaindé: Those films set our imaginations soaring. I made a list of the films that changed my life, which one day I’ll give to my children, and those two are on it. They make you cry and make you ten years older in an instant! They’re animated films that don’t take children for idiots. After watching Princess Mononoke, I said to myself, “I want to be that wild girl. I want to have her courage.”

Everyone always talks about the fact that you’re twins, but what do the sea and lightning have in common?

Naomi: We were never inseparable twins. We were never in the same class at school. We even went to dif- ferent secondary schools. And we don’t necessarily have the same friends!

Lisa-Kaindé: And Naomi left home very early. When you came back I saw the huge differences between us. I had a regular schedule, I was going to university and studying, but you were living it up! You were going to jazz concerts and singing the whole time. I was studying jazz, you were living it. Yours was an adult life, I was still a little girl. And then Ibeyi began. You came back home. We met Richard Russell.

Richard Russell has been your producer right from the start. What advice did a music legend like him give to artists who were barely 20 years old?

Lisa-Kaindé: “People think you have to listen to a lot of music to make an album. But what you have to do more than anything is read books.” That’s what Richard told us right at the start. He spoke at length about Damon Albarn [of Blur and Gorillaz] and the way he would shut himself up with a mountain of books to write. Because the hardest thing in music, he said, is the lyrics.

Yours are full of references and literary quotes, from the poetry of Claudia Rankine to the diary of Frida Kahlo...

Lisa-Kaindé: We come from an educated background and we’re very proud of that. Our grandfather was an art-history professor in Venezuela, our grandmother taught literature, and of course our father was a hugely talented musician. Not to forget our mother. Imagine the ef- fect of a mother’s words on her two children when she tells them “This book changed my life” or “That song changed my life.” From childhood onwards we were made aware of the power of artistic creation. And we felt it deep within us.

Can you talk about the track No Man Is Big Enough for My Arms, whose title comes from Widow Basquiat, Jennifer Clement’s book about the love story between her friend Suzanne Mallouk and Jean-Michel Basquiat?

Lisa-Kaindé: We were at Richard Russell’s country place, where I hap- pened on the book. It immediately attracted me because it was about Jean-Michel Basquiat. In the book, the narrator describes how, when she was only seven and her mother had hidden a soldier who was fleeing combat, he said to her just as he was leaving, “I’ll come back one day and marry you.” And the little girl replied, “No man is big enough for my arms.” On reading those lines, my jaw dropped. Who would dare say something like that today? What kind of adult woman has that kind of in- dependence with respect to men? The next day I met up with Naomi in the studio and said to her, “We’ve got a song.”

In the song, you also included part of a very powerful speech by Michelle Obama, in which she explains that a society can be judged by how it treats its little girls...

Naomi: While the song was taking shape in the studio, Donald Trump was elected president in the United States. The man who was caught boasting of grabbing women “by the pussy”...

In the track Deathless, you make reference to a much more per- sonal incident. As a teenager, Lisa, you were arrested by the police and treated like a petty criminal simply because of the colour of your skin.

Lisa-Kaindé: I understand that people can be racist. It’s simply be- cause they’re ignorant. It’s totally disgusting and unacceptable, but nonetheless I get it. It’s logical. What really shocked me that day was the total lack of reaction from all the people who were there and wit- nessed the scene. Who among them came to my aid? Who helped me pick up my things? Who had a kind word to say? They all just stood there like statues. Being immortal, “deathless” as I say in the track, is a way of taking back power, of doing something, of changing things. But I’m not talking about revolution here, just saying a kind word.