The copiousness of Nobuyoshi Araki’s work is like a vast personal diary that’s been forever bound with eroticism and death, fingering the passage of time with a voracious energy. The great Japanese photographer has created an exclusive series of nudes for Numéro Homme where the symbol of the heart is joined by recurring motifs from his world.

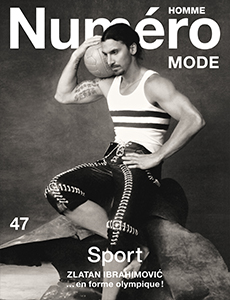

With smiling eyes, shaggy hair, a plump belly, round glasses and phenomenal energy, Nobuyoshi Araki walks around Tokyo at high speed, with a booming laugh and an irrepressible desire to be naughty. He strolls through life without a worry in the world, wearing his camera which he hasn’t been without since the age of 12… even though he likes to say the first photo he took was of his mother’s vagina when he was born. Perhaps this is where his obsession with the female sexual organ comes from.

After all it’s where Araki came from, like all men, and he wants to go back. The vagina was long the object of his photographic conquest right up to when he encountered love, and met his wife Yoko. At the time he was working at the famous Japanese agency, Dentsu, where he claims to have learnt everything that mattered in photography: “In this job, you take advantage of the work to promote yourself more than the product or your client […]. So I knew I had to get out quickly if I wanted to move into making art.” Yoko also worked at the agency; they fell in love and got married. On their honeymoon Araki’s camera was never far from his side, particularly during their most intimate moments. It was here he took the black and white photo (colour came later “to bring life”) that led to fame: a shot of his wife on the verge of orgasm.

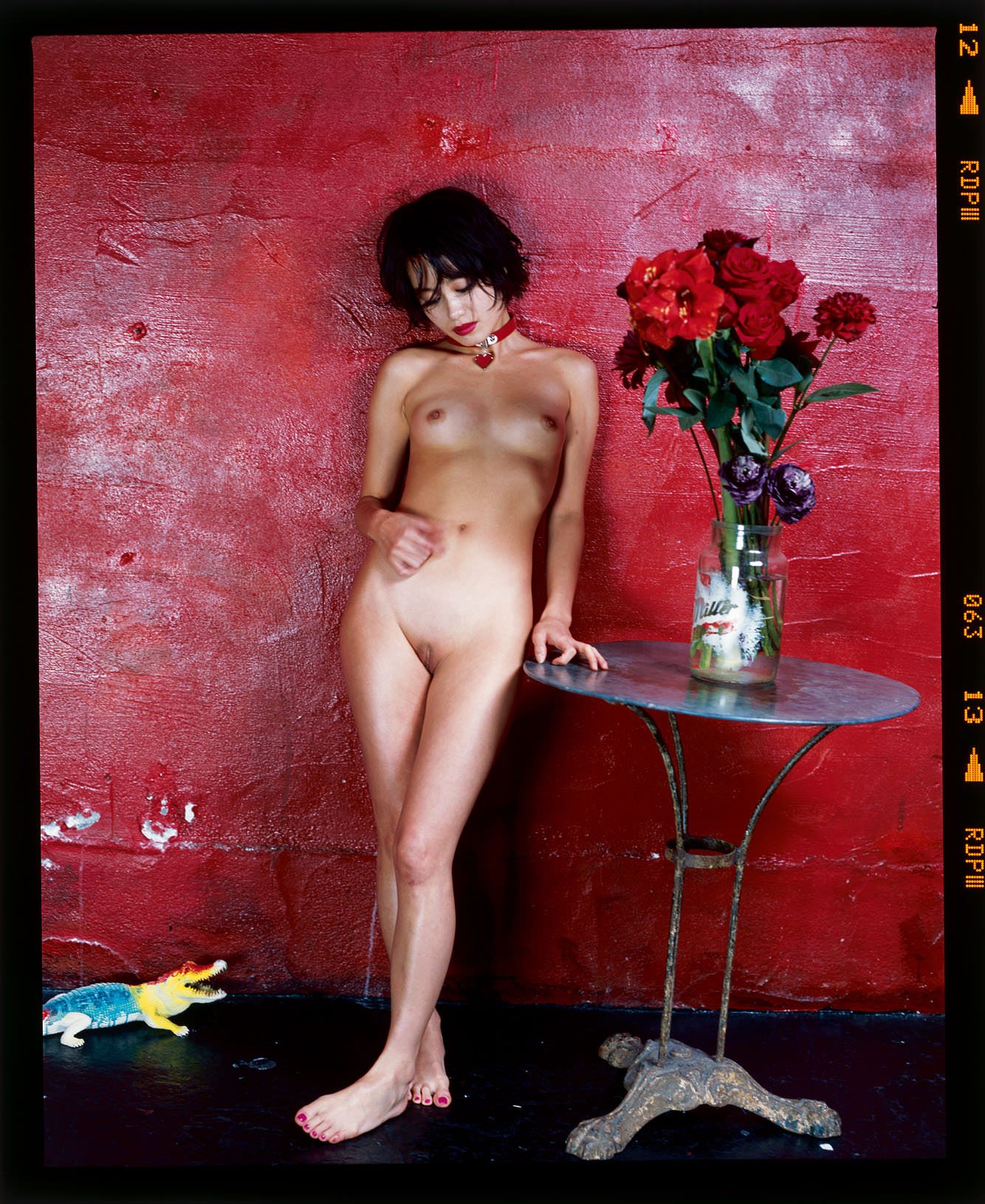

The crocodile is one of the alter egos of the artist, who was unable or unwilling to appear in the picture, and yet would be there in another form, on a smaller scale.

His photographs are the fragments of his life that only make sense when they follow in succession and answer each other. Sometimes a book is published a few weeks after a shoot, and this rapidity highlights the artist’s urgency to compile what he creates. Often Araki publishes them himself. His books allow him to compose the thread of his existence and undoubtedly to make sense of what he lives, or at least a certain fluidity. He assembles his raw, untouched images torn from real life. The books become a storyboard of his reality. His daily existence becomes part of a continuum in which he is placed as a central and exterior element, like the child to whom we tell a story, when in fact they are the protagonist.

The juxtaposition of photographs in Araki’s books is a composition of reality, even though they appear to be compiled so randomly. Everything looks perfectly normal, starting with his subjects, well his fetish subject: women, young women, most of whom see their time spent before the photographer’s lens as a liberating, transgressive experience allowing them to face their own taboos and discover their sexuality. They forget that the man behind the camera organises reality exactly as he wishes it to be, in a dynamic, almost joyful way. The shots look like scenes where wanton children make surprising discoveries, recklessly bursting into laughter: this is without a doubt fundamental to offsetting the pain of vertically thrown back heads, being bound with ropes, in positions that look incredibly uncomfortable, yet in theory are both sensual and sexual.

Before Araki, particularly in Japan, photography was used only for international reporting. By introducing personal sentiment and its total subjectivity, Araki transformed the 8th art and freed it, as much as the women he depicts. Photography could represent what all of us feel and be witness to the artist’s excesses, whatever they may be. Surely this is what characterises Araki, his lust for life and his need to live at full speed leaving a trace of everything he does at every instant. Araki’s personal diary is staggering in its scope, composed of more than 450 publications, books and magazines… diffused in Japan and across the globe. An exhibition can bring together up to 4000 prints. This gargantuan aspect fits the personality, who, like a manga hero, wants his life to be seen, just like all the women he loves, for years or for minutes. Beyond the recurring debate – based on legitimate observation – around whether his photos are art or porn, Araki questions intimacy. He’s long waltzed along the ever increasingly porous frontier between public and private, and this is what makes him a pioneer. Not to mention his vision of the female nude having been the first to stage the women’s body and genitalia this way. They’re no longer objects but landscapes – some of his nudes actually resembling a true still life work.

Araki says he binds women’s bodies, “because only the woman’s body can be knotted. I up tie women because I know I can’t tie up their souls.”

Known as kinbaku, this set of robe work, a genuine art form in Japanese culture, strives to valorise the body to bare its emotions. The kinbaku is associated with diverse sexual practices, from tantric activities to dance and martial arts. The dog collar in our series echoes the ropes used by Araki (that he long carried around with him, just in case…) to simulate strangulations of his subjects. Trying to understand why the artist would want to catch women’s souls and not let them go is another matter that maybe the rainbow crocodile could help us to elucidate. It’s a typical mise en abyme in his work, the crocodile being one of the alter egos of the artist, who was unable or unwilling to appear in the picture, and yet would be there in another form, on a smaller scale, where he could do everything or nothing. This crocodile comes from the incredible bestiary the artist has acquired over the years and keeps at his home. Araki affirms to “always needing company” to needing comrades around him, “because I often feel solitary and these monsters are my alter egos”. It’s almost like those children’s beds covered with so many teddy bears they bury the little boys and girls: a protective wall that helps them to fall sleep… But what is Araki so fearful of? What monsters peopled his childhood so that today he must still guard against loneliness?

Nobuyoshi Araki, solo exhibition from April 12th to September 5th at the musée Guimet, Paris.