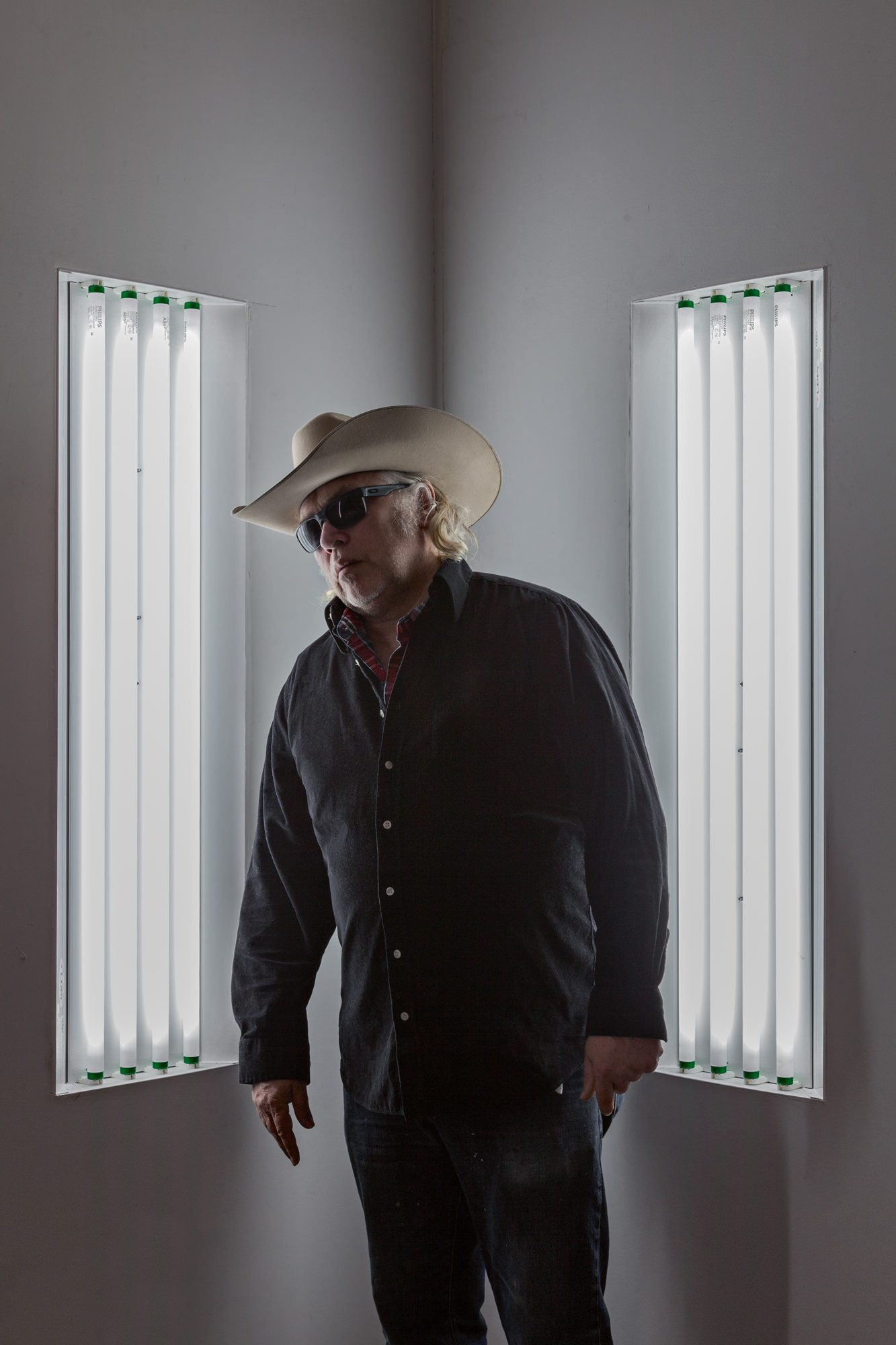

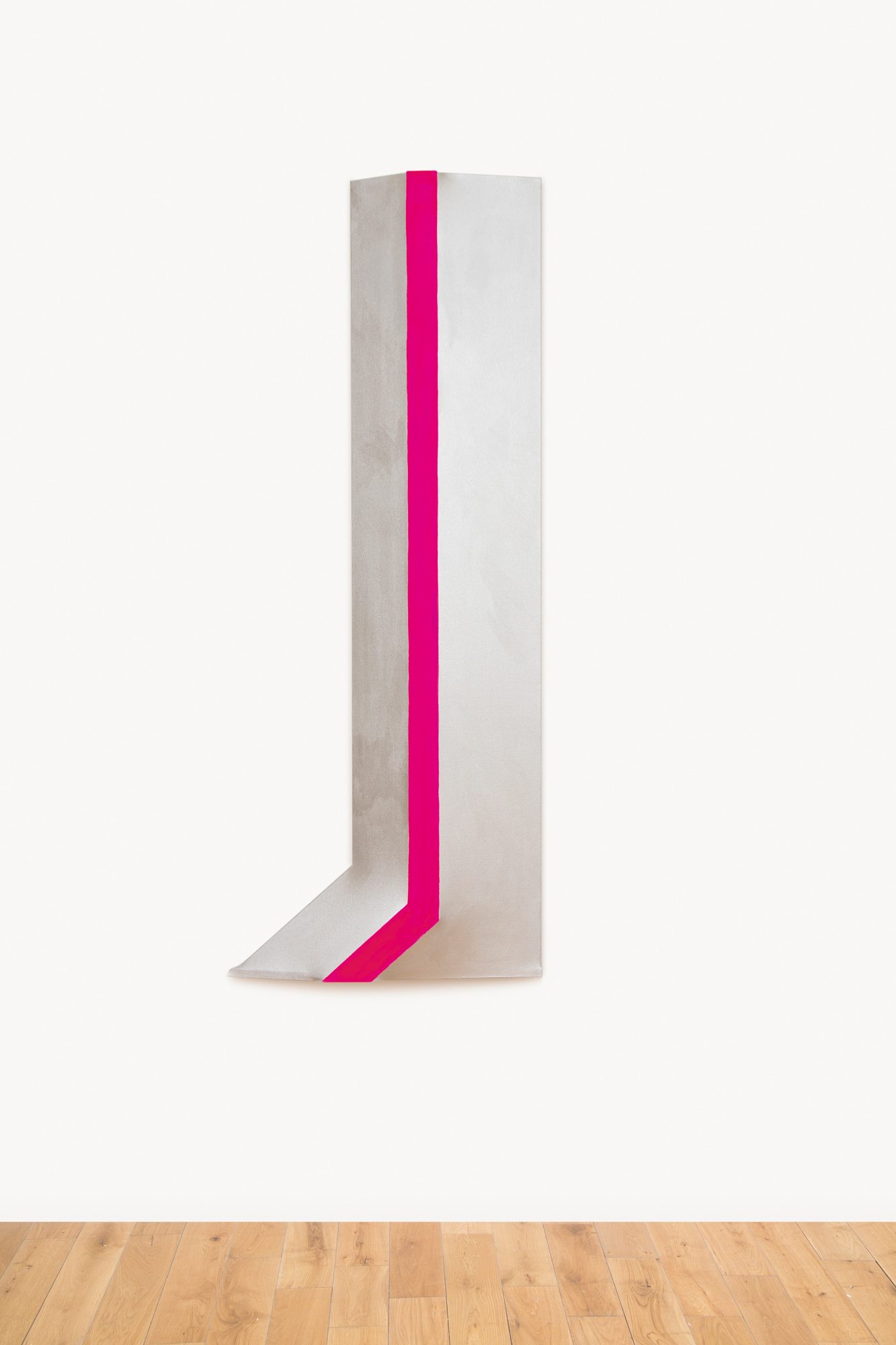

Blair Thurman’s website, which consists mainly of photos, shows us his childhood at The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, which at the time was directed by his mother, all the way up to today, in his studio in upstate New York, where he’s just as handy with a chainsaw as with a paintbrush. In this biographical photo album we see his close friends and the people who influenced him, like the late artist Steven Parrino, or Nam June Paik, for whom he formerly worked as studio director. At 55, Thurman has achieved success with his neon installations and his paintings that are almost sculptures, often comprising canvasses stretched onto chassis of different forms. France discovered him at Triple V and Frank Elbaz, but he’s been exhibiting all over the world these past few years, at Gagosian in New York, Peres Project in Berlin, or more recently at Almine Rech in Brussels and London last September. His work humorously combines American vernacular culture, post-minimalist formal codes and the conventions of the readymade.

Numéro: How did you become an artist?

Blair Thurman: I had a very fortunate childhood with respect to art. In my teenage years, I drifted away from it – typical 70s high school, sex, drugs, a lot of road trips to the beach. When the time came for me to find a profession, the only thing I was cut out to do really was to be an artist. Perhaps we had always assumed that’s what I would do. In Nova Scotia, where I went to school, there was a very strong art-history and conceptual program, but I felt I needed some kind of discipline, which I found in printmaking. I guess I was trying to pick up some kind of work ethic. It was labour intensive, but I discovered a lot of interesting things about seriality, modification, and image reversal – I always wound up liking the backwards plate more than the finished print. No matter which one I started with, it was always the other one that was better.

Who inspired you? What were your art references?

Of course I always liked Warhol – the Pop flatness – and also John Wesley for the same reasons. There are so many painters I admire and love. I was very spoiled as a child for this business in the sense that I was surrounded by a lot of beautiful 50s and 60s painting – the Pop flatness, and also Abstract Minimalism, which I never found that different, between a very flat Warhol and a monochrome. Here I mean a kind of dry awareness of oblivion that finds expression in painting, which derives from a manmade landscape with the predominance of reproduced and perfected forms. I give you the example of Richard Smith, a British painter, whose work I must have seen when I was five or six years old. The paintings were monumental, like a kind of 3D billboard, with minimal colour, a minimal surface, geometric cigarette boxes looming physically from the rectangle in relief, a kind of escape from the Greenbergian plane. I only realized much later, maybe a few years ago, how much influence Smith’s 3D paintings had on me. I remember seeing Stellas from the time and being very impressed with the monumentality, the aluminium paint − it was very sexy for a kid. I rushed to see the Stella retrospective at the Whitney recently – I had seen some of the works as a child and was familiar with most, but, seeing them in the flesh again, I found myself so inspired. As an artist I feel more akin to a used-car salesman, selling interesting models, rather than a new-car dealer. I recently read something that John Armleder said about how he felt that my work was a lot about customizing, and I also realized that there’s a lot of customizing in the hot-wheels influence – the Spectraflame paint, the way every new series would be painted or customized, modified in some way, like different ways of handling the same painting.

Are you a painter?

Well a lot of my work is layered on previous works. If I make a painting and I like it, I want to relive that because I enjoy painting, and you wind up with a natural lineage. Steve [Parrino] gave me a very useful bit of advice, one of many, which was to picture the best work of a favourite painter and then try to imagine my work hanging next to it. If you’re honest with yourself, it’s a really great test, which I still fail quite often.

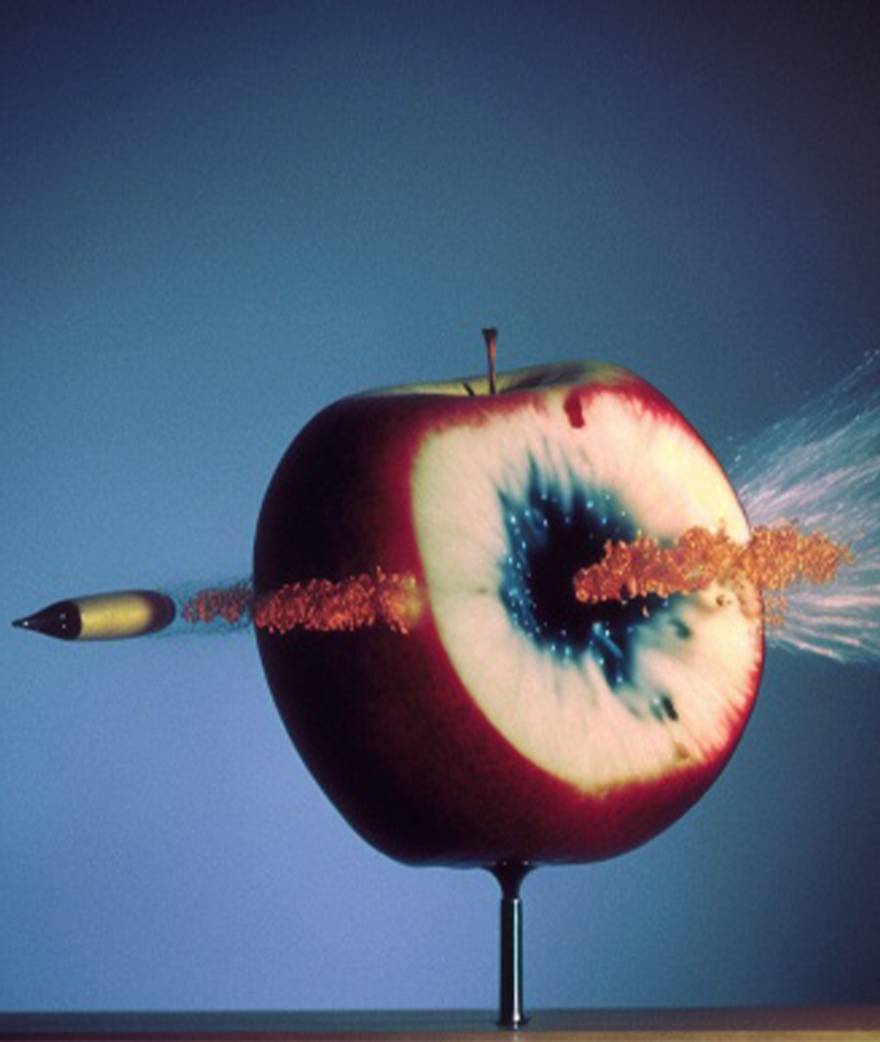

Cars, guns and their symbolism are the main subjects in your work. Why?

I have to disagree with you on that. I have a much broader interest in various aspects of culture at large.

You’re principally known for your neon works and your shaped canvasses. How do you shift from one medium to the other, and which are you most at home in?

I became really proficient in neon working with Nam June Paik, and then in my own work. Initially the neons were conceived more as atmosphere or environment for the paintings. Previously I had created painting soundtracks, like mix-tapes, which were audio complements for the same purpose. The difference between painting and neon is not so much an issue, they can accomplish similar ends. Aesthetically, the morphological difference isn’t so extreme as one might think. Sometimes I do a painting based on a neon that was based on a painting. Or I use the two together. They can both be very poetic, very nostalgic. Neon can have an age, too. Painting obviously is quieter, therefore a lot easier to live with.

What about the readymade aspect in your work?

As a student I invented a system of painting that I called “less-than” painting. The idea was an all-over matrix, like tiles of relatively simple rectangles, a colour or a simple shape. The object of it was to encourage a kind of a scan rather than a gaze. I realized after several painful years that this system was too heavy, too much theory. Around this same time, I was also experiencing a strong nostalgia for childhood aesthetics − toys, for example − and I made the connection that modular toy tracks, like Hot Wheels and slot-car tracks, were already achieving the same effect, but in a much lighter, more elegant way. Since then I’ve become more able to see the found-art solutions.

Are you inspired by movies or by songs?

Yes, I watch movies constantly. Two or three nights a week as a teenager I would go to a movie with my dad instead of doing my homework. There were a lot of retro theatres around Boston. Perhaps he was training me. Now I have to have a TV with movies on constantly.

Titles seem to be very important to you. How do you go about choosing them? And what would you say is their purpose for you?

I often find that the painters I really like seem to use great titles. The title is an opportunity for the artist to identify their position in relation to the viewer. Am I giving you the finger? Are we sharing a joke? Are we sharing a secret? Am I patting you on the head? Am I happy? Am I sad?

Do you feel you’re part of a new generation of artists, or that you belong to a certain group of artists?

I find I do my best work when confronting myself. And it’s not always that easy, even though I’ve been doing it for a long time. It takes particular conditions. I think I would find it very hard to focus if I was in the city, for example. I find openings can be very frantic. I’m not used to seeing so many people at one time. I have my “art family” – people I care about. I try to stay in close touch with them through Instagram or whatever. I do miss them, but I think that to do the work, actually you really have to be alone.

Who are you speaking to? Who would you say is your audience?

That family – those same 50 people. And all the people like them that I haven’t actually met, but who I’m very glad to know are out there

Is there anything you would you like to change, or to make people conscious of, through your art?

It’s an amazing feeling when you meet someone through your art and you immediately know that they understand you. It’s hard to imagine another line of work or way of life that contains that possibility.

Blair Thurman is represented in France by the galleries Triple V and Frank Elbaz. Thurman’s exhibition Mature Blonde is currently on show at the Almine Rech gallery in London, until 14 May.