Numéro art: When you first opened ten years ago, what kind of gallery model did you envisage?

Felipe Dmab: We started the São Paulo space in 2010 because we felt that a lot of fantastic Brazilian artists were under represented. The first two artists we started working with were Paulo Nazareth and Lucas Arruda, who both grew with us and are still represented by us today. In very different ways, neither of them quite fitted into the Brazilian scene, and both addressed political concerns in a very conceptual way. Radical artists doing that kind of work were considered scary, especially in Brazil. An artist like Sonia Gomes was a complete outsider. It’s been wonderful to see her grow so much. We also understood that São Paulo had the potential to enter into dialogue with the world in a way that wasn’t happening. That’s why we started our residencies pro- gramme, inviting artists from all over the word – Asia, Iceland, as well as France, in the person of Neïl Beloufa.

Matthew Wood: We are storytellers. It’s our social mission. The significance of being a gallerist is your relationship to the artists, to their vision, to their message, the way you carry that message into the world, the extent to which you facilitate a wider reading or accessability to a wider public. It’s very evangelical, in the original sense. Sometimes art bothers you – you don’t like the message. And that’s interesting. You have to spread the message anyway, because the fact it bothers you means it’s powerful or relevant. There’s lot of good art out there I don’t like, it makes me unconfortable. But you still have to tell the story.Pedro Mendes: The role of an artist is to transform the way we see the world, while the gallerist’s role is to be the translator of that idea and to give visibility to it.

FD: The role of art is to transport us to another dimension of ourselves and of the world around us. Art helps to reveal and rethink the world, changing who we are and the way we behave in the world. It can sometimes be political and open your eyes to a situation around you. It can sometimes open new doors inside you. Artists should be able to grant you access to parts of yourself you couldn’t access before. That’s the magic of what art can do.

Which artists are you particularly close to?

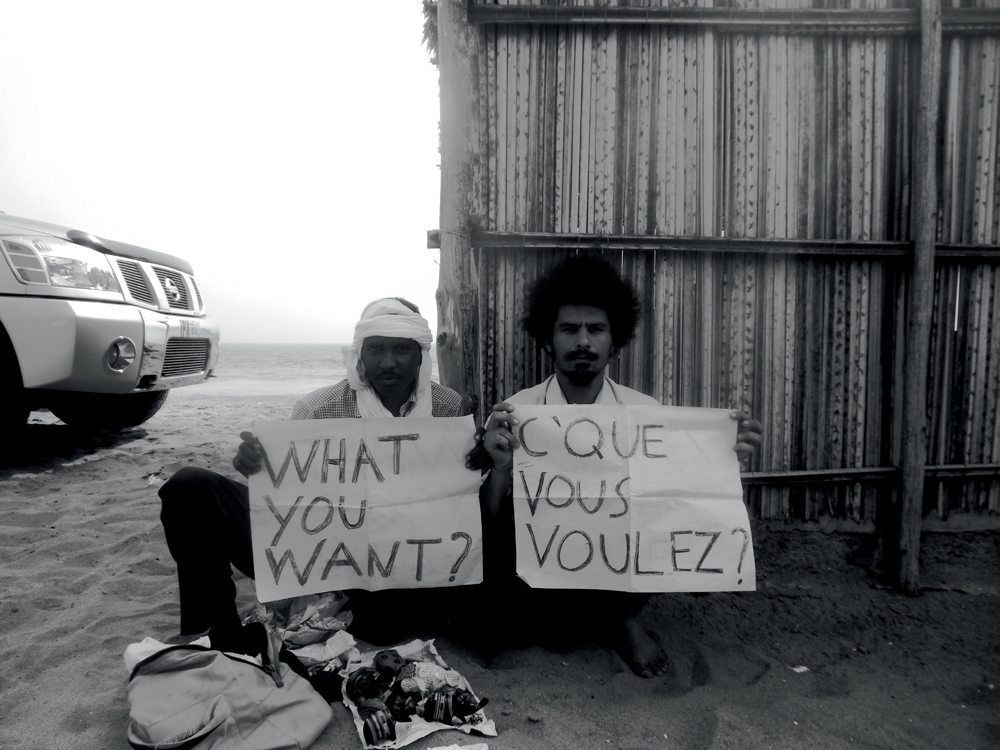

MW: The first artist that comes to mind is Paulo Nazareth. I met Paulo before we had the gallery. Pedro and I had an artist’s residency, and he was in our first group of residents back around 2007. As soon as I met him I knew I was dealing with someone different. He is totally sui generis. His practice is a complete practice – there’s no part of his life that isn’t touched by his art. Even back then, he was already telling me about a project that would involve his living according to very simple promises, almost like a code of conduct. One of the promises was that he would never wear shoes, only sandals, which was a form of social expression, because the poor in South America only wear flip flops. When he was growing up, he didn’t have shoes, only flip flops. As an adult, he didn’t want his feet to be bound up. I think he finds it terrifying. He wanted his foot to be contact with the earth. But it’s hard to wear only flip flops when you’re travelling all round the planet. He visited some- thing like 55 countries. It’s a real commitment. And then he told me he was going to walk to New York city when I got him a residency there. His work was already dealing with the idea of the diaspora and Black identity. We were actually the first gallery in Brazil to work with a Black artist, back in 2010. So I thought that what was happening in the US with respect to African-American culture could be important for him. But he didn’t want to take a flight or even a bus. “I only walk. That’s my thing.” So on top of wearing flip flops, he walks places. The next promise was that he would never wash his feet. Because he was collecting the dirt from all the different countries and using his foot as a conceptual painting, a canvas to reunite all the countries he had visited, as well as a reference to Homo sapiens walking out of Africa – a meta-reference to humanity’s common origin, we’re all brothers and sisters. He never got a cellphone by the way. And he never carries cash.

Your gallery has really reshuffled the cards of contemporary art in Brazil. What was the context at the time?

MW: The Neo-Concrete movement was such a big thing in Brazil. I think it partly arose in response to the military dictatorship, because the best way to deal with artistic censorship is to become an abstract painter, if you think about it. You can put big cubes on top of small ones, when what you’re really talking about is oppression. But dictators are generally so stupid they don’t notice. There was also a real prohibition on painting. “Painting is dead,” everyone kept saying. But painting never died, it’s just that everyone who was doing it was sidelined. And by extension everyone who was making what you’d call “craft.” So there were extraordinary painters like Lucas Arruda or “craft” artists like Sonia Gomes who were considered outsiders. We wanted to represent them

Pedro Mendes: Artists like Paulo and Sonia were not part of the establishment, they didn’t follow the traditional path whereby artists come out of universities, with a very specific training that encourages a very conceptual process. They were “simple,” trying to read the truth. I mean Paulo was perhaps a little bit versed in Fluxus and the German 60s and 70s, but Sonia, who was really trying to tell her personal story, was simply born an artist, with a creative gift, so those kinds of construction and typologies were coming straight from her guts. Sonia was very close to my sister – I’ve known her for 30 years. I was really carrying Sonia around in Paris when I was studying there, basically ringing the bell at all the little galleries in Saint-Germain, tacky little galleries, tell- ing them that they should show her, that she was a great artist, though I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. I was trying to help her. I remember an afternoon in the café at the Louvre. Sonia was always transforming textiles, and that day she was wearing a beautiful shawl. We sat down with this very influential woman, who at the time was a scholar and the trustee of a museum. And the woman said to Sonia, “That shawl is beautiful, I really like it. Where can I buy one?” Sonia wanted to stay in Paris, she was in love with the city, and I could see her calculating how much she’d need to prolong her stay. And so she said to the woman, “Listen, you can have it for $300.” [Laughs.] Sonia was a sort of adventurer, a living artwork in many ways.

MW: Sonia made these wild sculptures from just a single piece of wire, which sounds simple but really isn’t. When you see her make them, it’s like she’s dancing with them.

Can we talk a little about Solange Pessoa? Her work seems to get right down to the essential.

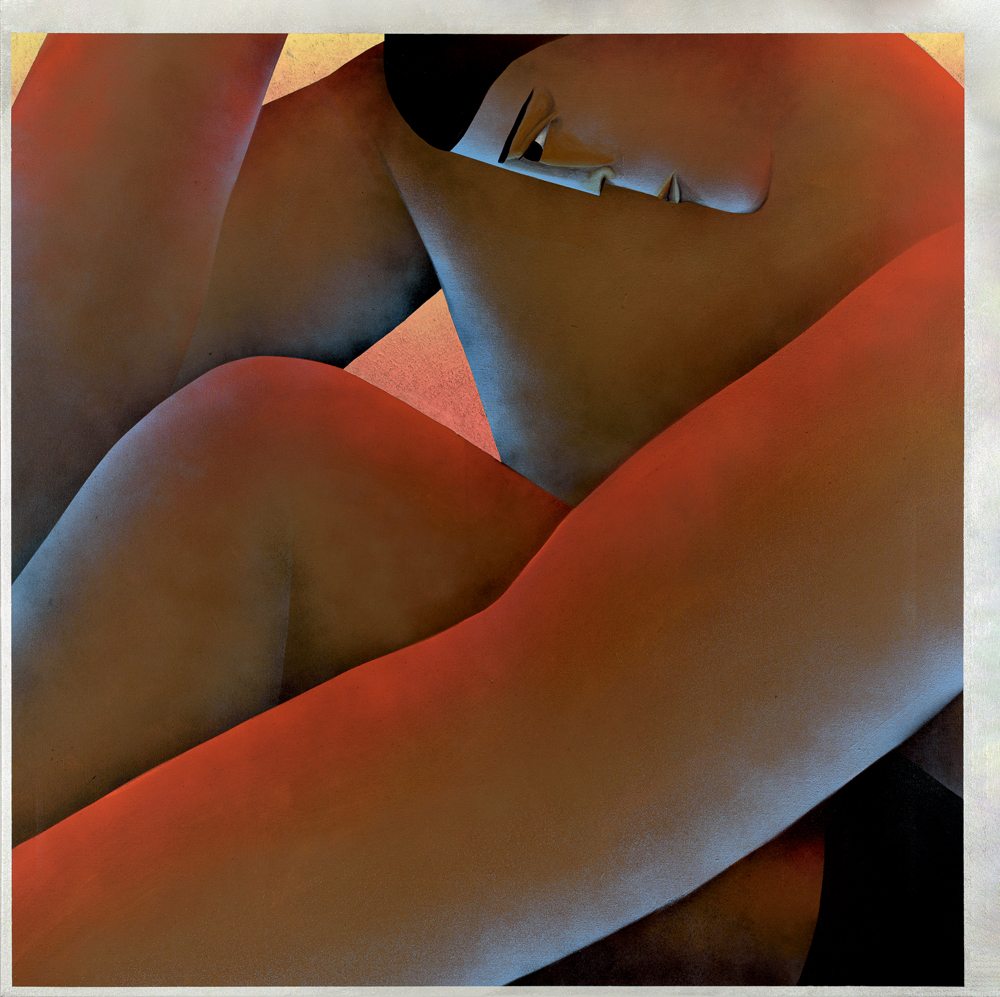

MW: You could say essential, yeah. One of the things we really care about is painting, painting as a direct window onto poetry. And we have a real engagement with artists of the diaspora who talk about Black identities in Brazil. Paulo Nazareth really talks about the human experience, but when he talks about the Black experience it’s in a very conceptual and meta way. Sonia Gomes talks about her personal identities. Solange’s work is like the most primitive iteration of what something can be, similar to Louise Bourgeois. She builds up spiritual spaces for someone to have a vision. For this, she uses essential materials like feathers, hair, blood and bones. She makes these strange white clay vessels that seem to come from another time. I’ve always felt deeply attracted to ceramics and works that refer to nature. Nature became kind of boring to a lot of people. It didn’t seem like a radical idea. In the 20th century, art was an urban thing: you think of places like SoHo, the Dadaists in Paris, the London scene, all these city people living in lofts doing coke, the underground, Andy Warhol... Whereas in the 19th century, you think of “plein air” art, the école de Barbizon and so on. It’s funny, culture goes back and forth, like you’re on a rollercoaster ride. Today I think it’s important to remind people that, yes, art is urban, but it can also be natural. The artist can be wild, and we have to remember that too, because the urban artist can become a neurotic artist.

The Gallery Mendes Wood Dm based in São Paulo, Bruxelles and New York